Source: Nature 405, 276–277 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35012676

Click here for the article as .pdf

By Mark Benecke / Book review

A Fly for the Prosecution: How Insect Evidence Helps Solve Crimes

by M. Lee Goff

"I didn't think anyone would actually be interested in reading about my cases," wrote Lee Goff about A Fly for the Prosecution, his first popular-science book. Such a lack of interest, however, was unlikely, as Goff is one of a small number of scientists who work out how long a corpse has been dead by using maggots and other creepy crime-scene reconstruction assistants. Furthermore, his lectures and workshops are constantly overcrowded and his sense of humour, combined with scientific accuracy, makes him the darling of his various audiences.

Although forensic entomology has a certain fascination for the public, any forensic pathologist will tell you that it is much more entertaining to read about cases than to collect live arthropods from decaying human corpses. This is where Goff's book comes in -- it is a colourful collection of forensic entomology research and cases (mostly his own in Hawaii), along with personal thoughts about how to deal with violent death and decay, and the story of his life.

An expert on mites, Goff stumbled into forensic entomology after hearing a talk about the decompositional patterns of pigs in 1981. He quit his job at a local museum and accepted a position at the College of Tropical Agriculture in Hawaii. Soon after, he and a handful of colleagues, who were either researching the activity of insects on animal cadavers or looking into the use of entomology in criminal investigations, set up an informal group called the Council of American Forensic Entomologists (CAFE). It is highly enjoyable to follow motorcycling arthropod specialist Lee Goff -- at that time, with his beard, earring and shaggy hair -- to formal forensic academy meetings, into the FBI Academy, in front of highly offensive US attorneys in murder trials, and away from the preparations of a peaceful New Year's Eve dinner to collect evidence at a crime scene. Thanks to the work of CAFE members, the method has grown in popularity among US forensic pathologists, forensic scientists and the police, until now the FBI Academy includes an annual arthropod collection class in their course "Recovery of Decomposed Bodies". The CAFE-edited book Entomology and Death: A Procedural Guide (Joyce's Print Shop, 1990) was a collection of practical information on the subject.

One of the most valuable points made in A Fly for the Prosecution is how different the characteristics of insect populations are in contrasting habitats such as corpses that are wrapped or burned, those hanging above ground compared with buried ones, and those poisoned with cocaine or with other drugs. This high variability of most biological processes is not only hard to explain in front of a jury, it also dampens the enthusiasm of many students and beginners. Goff sheds light on the limits of the method, stressing that forensic entomology needs experienced practitioners. As he points out, any investigation starts to get frustrating the moment identification of an uncommon arthropod species has to meet a deadline set by a subpoena instead of by common sense.

It can be difficult to persuade research agencies of the need for additional scientific studies, for example on the development of local arthropods at different temperature levels, on the identification of toxins produced by insects that have fed on corpses, and on DNA typing of insects. Therefore, it has taken years to bring the method into routine use in forensics. It is thanks to Goff and his US colleagues that forensic entomology is now widely known as an adequate and highly effective tool in difficult questions concerning the time of death and related matters of criminal investigation. Goff's book is the culmination of this effort.

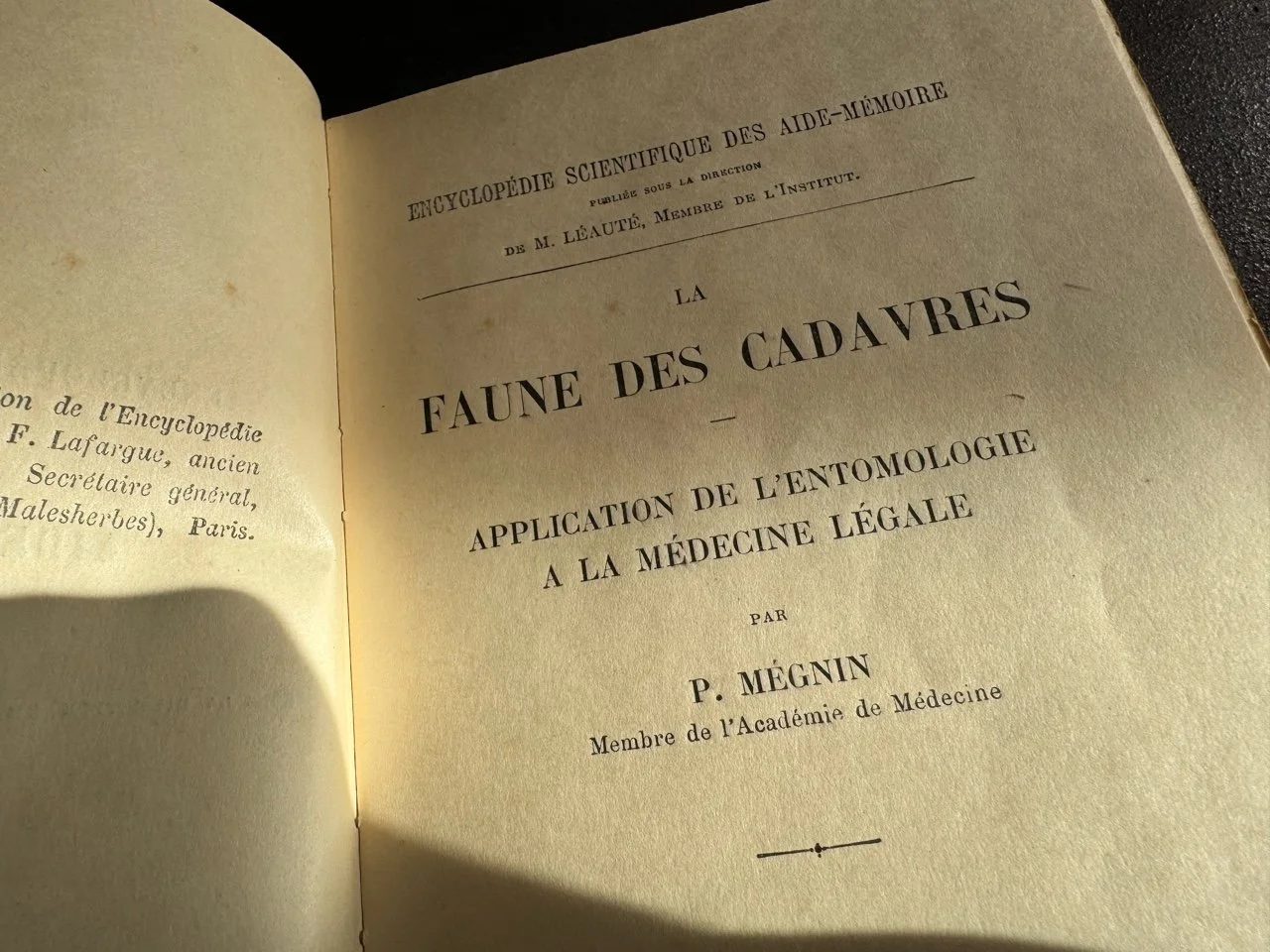

The method was discovered and pioneered in Central Europe 150 years ago. In Europe and Asia, where the older generation tends to view any popularization of science as suspicious and unnecessary, forensic entomology was kept alive after the war by only four scientists. Such historical details are only briefly mentioned by Goff. For the same reason, the use of non-metric units and Americanized species names, such as Phaenicia instead of Lucilia , is understandable. However, the contributions of Russian, Belgian, French, Finnish, Canadian and German researchers should not be underestimated. Therefore, and to get additional perspectives into forensic entomology, I would recommend three further recent publications. One is a special issue of the journal Forensic Science International on the subject (of which I am the guest editor), which will also include the latest research results to be presented at an international meeting of forensic entomologists held in Brazil in August 2000 (http://www.benecke.com/feauthor.html ). There is also a well-researched popular-science book by Jessica Snyder-Sachs about to be published, and the scientific handbook Entomological Evidence: The Utility of Arthropods in Legal Investigations (CRC Press, 2000). Meanwhile, enjoy Goff's beautifully illustrated, scientifically sound and entertaining story.

Author Affiliation(s):

Mark Benecke is in the Forensic Biology ResearchUnit, Institute for Zoology, University of Cologne, Cologne 50923, Germany.